Katran’s role in the field of contemporary art is that of an inventor artist. In football terms, he is an obvious playmaker – a creative player with ideas, who sets the field for attack, quickly orchestrating the moves and knowing when to change tack. Among Katran’s existing artistic inventions are the soundwave-shaped sculptures, representing the word “art” in series of world languages, on permanent display at Les Jardins d’Etretat, France; a station generating Free Time; the act of throwing a deadly meteorite off its course, thus, preventing a collision with Planet Earth; and finally, a plan of cultural exchange with exoplanet humanoids from the Cygnus constellation, and much else.

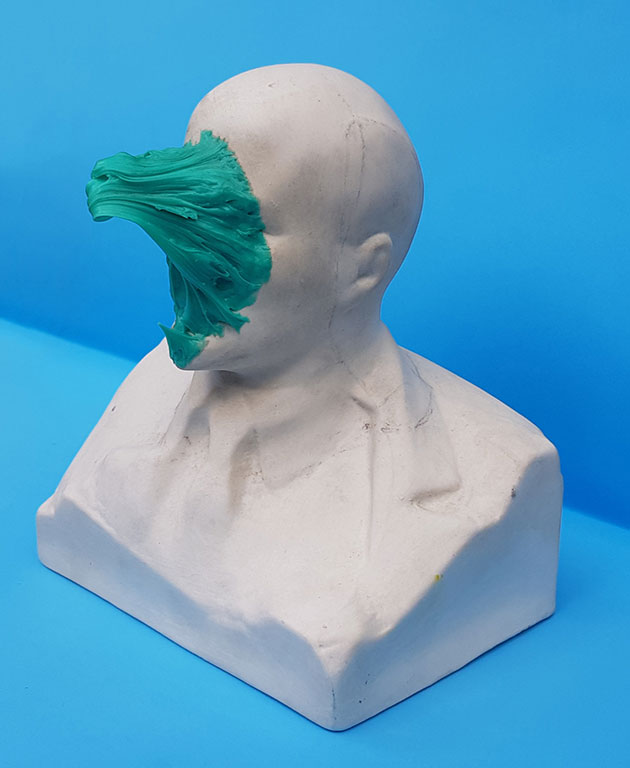

However, Katran’s major invention, and namely, his theory of post-vandalism, is demonstrated in the series presented here. Despite its provocative name, the theory peacefully rests on humanistic foundations. Whilst vandalism is a destructive act of aggression and obscurantism, post-vandalism is, contrariwise, the process of reclaiming objects and relevant situations for the realm of culture. The act of post-vandalism projects the situation of crisis and deviation into the sphere of Dadaist play and irony. It is important to understand that absurdist post-vandalist works are not mocking the heroes of bygone times. On the contrary, they are an orchestrated, intended act of topsy-turvying, a change of perspective, an invitation to philosophical reflection.”

Sergey Katran: “The American Columbus demolition spree and the Ukrainian Lenin demolition spree; sculptures doused in paint, with their fragments sawn off; the Egyptian Sphinx mutilated by Napoleonic artillerymen, Buddha statues blown up to pieces in Afghanistan; destroyed monuments of Palmira – all these are the ominous patterns of ideological extremism, or barbaric destruction tinged with a certain degree of complacent bravado. In my series, pre-meditated cultural post-vandalism emerges as the opposition to the unruly spontaneous vandalism. This artistic phenomenon has not yet been fully explored, or systematically studied, however, it has a certain backstory. Let us remember Marcel Duchamp. In 1919, having added elegant moustache to the postcard image of Mona Lisa, he introduced, as Kazimir Malevich might have said, an “additional element” into the image. Through this iconoclastic gesture, Duchamp did not only appropriate the great work of Leonardo, but also changed the perception of it. The witty act did away with “snobbish and culturological scum”, changing the optics of perception of the famous masterpiece. And no one will now rebuke Duchamp for not respecting culture. He took a reproduction and repurposed it for his own aesthetic goals. A more radical act of cultural vandalism was perpetrated by the artist Alexander Brener, who in 1997 sprayed a green dollar sign over Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematisme (1920-1927) in the Stedelijk Museum of Modern Art in Asterdam. Finally, the pinnacle of absurdist vandalism in popular culture found its expression in the Joker’s takeover of the Gotham Museum of Art (Batman, 1989).

However, my theory of post-vandalism addresses a different issue. Yes, it partly relies on the “media” and energy inherent in vandalism and places the transformed objects into a contemporary cultural context. The post-vandalism’s goal is to change the optics of the observer, to remove superfluous elements from the work of art and to approach it from a different angle. At the same time, post-vandalism is characterized by lively and hooligan-like, transgressive action, driven by irony, and critique of ideology.

Written by Vladimir Bogdanov

Translation: Irene Kukota